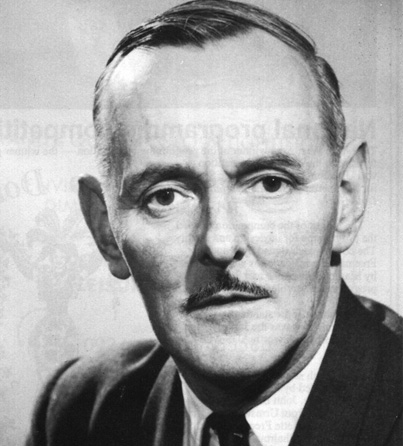

Eric Maschwitz was a man of great charm who new simply everybody in show-business. He was first married to Hermione Gingold; he adapted French comedies like Thirteen For Dinner; he wrote the book and lyrics for numerous musicals, amongst them Balalaika, Summer Song and Zip Goes a Million; he was Director of Variety at the BBC and inspired such creations as In Town Tonight and Café Collette. He had also, at one time or another, edited the Radio Times, turned The Ghost Train into a musical and written the words of "A Nightingale Sang In Berkeley Square" and "These Foolish Things". In 1958, at the beginning of the battle of the TV ratings in UK between ITV and the BBC, Eric Maschwitz was to become Head of Light entertainment. At the time of his appointment he said, "I belong to an earlier generation but that doesn't mean I'm blind to new kinds of popular music. You have to recognise that there is a young audience." About the job he said, "I don't think the BBC is a cultural organisation. We've got to please the people. The job of a man putting on a show is to get an audience. The Corporation want me to be an adviser, father-confessor and energiser to the young staff. There's only one job for an older man - at the top - as an executive. In his autobiography Eric states: "As the number of my musical plays increased so developed my relationship with amateur operatic companies. In this nation of "small shopkeepers" it is reckoned that no fewer than 100,000 performers give up their spare time to the rehearsal and performance of musical works ranging from revue, 6through musical comedy and operetta, to grand opera." "As soon as the war was over I began to give a large part of my time to "the amateurs;" I enjoyed working with them; the whole movement has a vitality and a gusto which seems to be vanishing from the professional theatre. With George Posford I wrote Masquerade for the Baltic Operatic Society. One after another, I adapted by own existing plays to amateur requirements (simplified scenery and additional opportunities for the use of a large chorus). With Bernard Grun I repeated the process with the work of other authors: we prepared amateur versions of Die Fledermaus, Night In Venice, The Dubarry and White Horse Inn." "Since the war I have made a point of attending some 20 amateur performances of my work every season, thereby finding great enjoyment and making many friends. The standard of production and performance is, in general, very high. At least one of my own plays has been better presented by an amateur company that its professional form." This is real show-business - an unpaid replica of life behind the scenes in the professional theatre - the stage slang, the etiquette, the bouquets, the telegrams, the 'first-night-nerves' - even the superstitions. For a succession of magical evenings Miss Smith becomes Evelyn Laye, Mr Jones a Bruce Trent or Norman Wisdom. There are dressing-room parties, the eager scanning of the newspapers for the "notices", the regretful farewells at the end of the run. The day after that exciting last night Miss Smith is once more the secretary, Mr Jones th4e manager of the bank. These people have a deep true love of the Theatre which is, alas, too often lacking in the professionals of today."

|

||

|

||